Selectors and Specificity

In this kata, we’re going to answer the following questions:(link to the complete list of questions)

Base selectors🔗

Before learning a lot of properties and values, let’s focus on the selector part of CSS rules. The selector points to the HTML elements that you want to style. There are a lot of selectors, you will need to know them well to read CSS fluently. Here are the five main ones:

- *, the universal selector

- It will select all DOM nodes.

- h1, the type selector

- It will select DOM nodes of the given HTML type. The one we’ve used so far.

- .example, the class selector

- It will select all elements with the class="example" attribute.

- #example, the ID selector

- It will select the element having the id="example" ID.

- [attr="value"], the attribute selector

- It will select all element having the given attribute value.

Task: turn the label red by selecting it in every possible way we’ve seen!

As IDs are unique in a HTML document, using the ID selector is not great because the associated CSS declarations cannot be reused. It costs you nothing to use a class instead, so use class selectors instead of ID selectors.

Type selectors are a bit too broad as they select all HTML tags of this type. It was great when web pages were light and small, but today web pages contain a lot of elements with rich UI interfaces. For instance, writing a rule with the a selector will impact the look of your links in the navigation menu, in your main content and in your footer. Everywhere on every page. Furthermore, the style is easier to reuse with a class. What about styling a link that looks like a button? Use the .button class on the a tag when you need to. So use class selectors instead of type selectors.

Attribute selectors are a bit of a niche, usually it is more efficient to add a class than a custom HTML attribute. You got it, use classes whenever possible.

Combining selectors🔗

You can combine selectors to create more complex ones:

- .a, .b, the list/OR combinator

- This will select elements that have the a class or elements that have the b class

- .a.b, the AND combinator

- This will select elements that have both classes: class="a b"

- .a .b, the descendant combinator

- This will select elements having the b class inside elements having the a class

- .a > .b, the direct child combinator

- This will select elements having the b class that are direct children of elements having the a class

- .a ~ .b, the general sibling child combinator

- This will select elements having the b class that follow elements having the a class and that share the same parent node as the a class.

- .a + .b, the adjacent sibling child combinator

- This will select elements having the b class that are right after an element having the a class and that shares the same parent node.

Task: turn the node B (only!) red by every possible way we’ve seen!

Pseudo-classes and pseudo-elements🔗

Peusdo-classes allow us to select elements based on states or informations not present in the DOM. Here is a complete list of pseudo-classes and here are the ones you should know:

- :hover

- Selects the element that is being hovered

- :focus

- Selects the interactive element that is being focused (such as a button)

- :active

- Selects the interactive element that is active (such as when you click on a button)

- :visited

- Specific to links, applies if the link has already been visited by the user

- :checked

- Specific to checkbox inputs, applies if the checkbox is checked

- :disabled

- Selects the interactive element if it is disabled (such as a disabled input)

- .list:first-child, .list:last-child

- Selects the first element or last element among its siblings

- .list:nth-child(even), .list:nth-child(odd), .list:nth-child(5n)

- Selects every nth element among its siblings

- :not(p)

- Negates a selector

Peusdo-elements allow us to select entities that are not present in the HTML. Here is a complete list of pseudo-elements and here are the ones you should know:

- ::before, ::after

- If the content property is set, creates a pseudo-element that is the first/last child of the selected element. It is often used to add cosmetic content.

- ::placeholder

- Selects the placeholder text in an input

Task: use a lot of selectors we’ve seen!

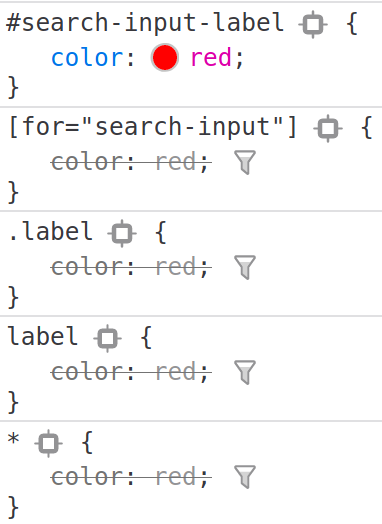

All of this is great. But with multiple colors applied to the same element, how does the browser knows which rule to apply???

Specificty🔗

Specificity determines which CSS rule is applied by the browser. If two selectors apply to the same element, the one with the higher specificity wins.

The rules to win the specificity wars are:

- Here is the selectors hierarchy:

- Inline style beats ID selectors.

- ID selectors are more specific than classes and pseudo-classes.

- Classes and pseudo-classes win over type and pseudo-elements selectors.

- The universal selector (*) and combinators (>, :not()) have no impact on specificity.

- A more specific selector beats any number of less specific selectors. For instance, .list is more specific than div ul li.

- Increasing the number of selectors will result in higher specificity. .list.link is more specific than .list and .link.

- If two selectors have the same specificity, the last rule read by the browser wins.

The !important keyword

Although !important has nothing to do with the specificity of a selector, it is good to know that a declaration using !important overrides any normal declaration. When two conflicting declarations have the !important keyword, the declaration with a greater specificity wins.

A valid use case of the !important keyword is to override design libraries using very specific selectors that you have no control over.

Examples

Here is a good website to compute the specificity of a selector: Specificity Calculator. Below are some examples combining different selectors that we’ve seen:

The problem with specificity is that it becomes increasingly difficult to override a selector when its specificity increases. That’s why ID selectors, inline styles and the !important keyword are considered bad practice: it becomes almost impossible to override them.

Task: aside from the fact that this design is ugly, refactor the code with what we’ve seen so far to use only classes for the same design

In fact, you can build whole websites without going further than a specificity of 2 classes and a pseudo-class. Let me demonstrate that.

When you select an element, you want to either:

- Select it directly (class)

- Select it in the context of a parent (class of the relevant parent node or pseudo-class like :first-child)

- Select it in a certain state (pseudo-class)

In the worst case scenario, you will need to select an element in a certain state in the context of its parent, so a combination of the three item aboves. Thus, any selector more specific than 2 classes and a pseudo-class is a code smell.

What is a good selector?🔗

So, we’ve seen that a good selector should have a low specificity. But sometimes it is possible to achieve the same result with different selectors. Classic example:

What is the best selector among those five versions? A good selector conveys the design intention and thus will be more resilient to changes. Here the design intention is not clear so it’s difficult to pick one, but let’s analyze the intentions:

- .article is probably not a good selector because I probably don’t want to set the margin on all articles. What if I want to use the .article class on a lonely article in another page?

- .articles-list > * seems better because the margin is applied in the context of the list. But what if I add a title in the .articles-list section or some pagination buttons at the bottom? In this case I may not like the margin given to all children by this selector.

- .articles-list .article seems better than the previous one. But there’s still a margin after the last element that might interfere with content after this section

- .article:not(:last-child) solves the last margin problem but is not scoped to the list (same problem as .article)

- .articles-list > :not(:last-child) is probably what I would go for, but that’s still making assumptions on the design intentions.

As we’ve seen, choosing the right selector may not be easy. Overall, try this:

- Ask yourself "what is the intention?"

- If the intention is not clear, ask your designer

- If it’s still not clear, pick your best guess by confronting your code to edge cases or by trying to imagine what happens if you reuse this code somewhere else.

What I should remember🔗

- The simple selectors: *, type, .class, #id and [attr]. Always prefer classes to other selectors.

- The combinators: .a, .b, .a.b, .a .b, .a > .b, .a ~ .b and .a + .b.

- The pseudo-classes: :hover, :focus, :active, :visited, :disabled, :checked, :first-child, :last-child, :nth-child(even/odd), :not()...

- The pseudo-elements: ::before, ::after, ::placeholder.

- How specificity works.

- A good selector has a low specificity and conveys the design intention.